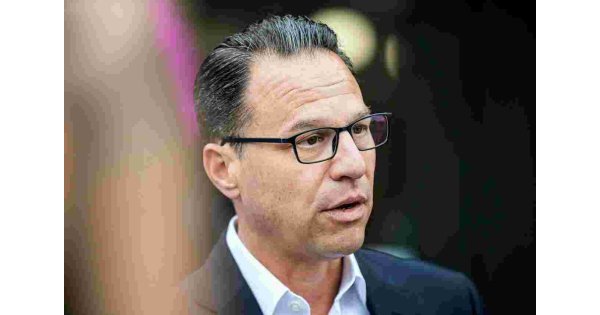

Han Dong-hoon’s resignation as leader of South Korea’s ruling People Power Party reverberates through the nation as the constitutional court begins its review of President Yoon Suk Yeol’s impeachment. Han’s dramatic decision to support the impeachment, following Yoon’s controversial imposition of martial law, rendered his position untenable. At a press conference, a visibly distraught Han declared, “Martial law in the advanced nation that is South Korea, in 2024. How angry and disappointed must you have all been?” His remorse was palpable, his voice heavy with the weight of his decision.

His justification for this unprecedented betrayal of his former political mentor centered on the gravity of Yoon’s actions. He defended his support of the impeachment, stating that remaining silent would amount to condoning the illegal mobilization of the military. The image of defending an act that threatened potential bloodshed between citizens and soldiers, he argued, was a betrayal of South Korea itself. He emphasized his attempts to avert impeachment, claiming that only his shortcomings prevented a less drastic solution. “I tried in every possible way to find a better path for this country other than impeachment, but in the end, I could not. It’s all because of my shortcomings. I’m sorry,” he concluded, his voice choked with emotion.

The resignation signifies the complete fracturing of a once-unbreakable alliance between Han and Yoon, forged during their years together in the prosecution service. The seeds of discord were sown earlier this year when Han publicly suggested that President Yoon and his wife should apologize for allegations of receiving a luxury gift. However, the final break arrived with the revelation that Han was among those targeted for arrest during Yoon’s fleeting martial law declaration.

This arrest order became the catalyst for Han's dramatic shift. He openly urged fellow ruling party members to vote for impeachment, characterizing Yoon’s actions as a grave threat to South Korea’s democracy. This marked a stunning reversal for a man who once served as Yoon’s justice minister and was considered his closest confidante. The rift exposes the deeper fault lines within South Korea’s conservative movement, highlighting a generational clash between Yoon's traditional power base and Han's younger, reform-minded faction.

The constitutional court's commencement of the impeachment review adds urgency to the situation. All six justices attended the initial meeting, initiating a process that could take up to six months to conclude. The court’s decision will determine Yoon’s fate – removal from office or reinstatement. Dismissal would trigger a national election within 60 days, with Prime Minister Han Duck-soo serving as acting president in the interim. Yoon’s presidential powers are currently suspended.

Meanwhile, the shadow of potential criminal charges hangs over Yoon and several senior officials. They face accusations of insurrection, abuse of authority, and obstructing citizens’ rights during the brief martial law period. A joint investigation team, comprising members from the police, the defence ministry, and an anti-corruption agency, plans to question Yoon this week. While Yonhap news reported the planned questioning for Wednesday, confirmation from the investigators’ office remains pending. The urgency surrounding this investigation is amplified by Yoon’s failure to appear for a summons from a separate prosecutorial investigation on Sunday.

The six-hour episode of martial law, announced in a late-night national address on December 3rd, remains a jarring memory. Yoon accused the opposition of crippling the government through “anti-state activities,” justifying the deployment of hundreds of troops and police officers to the national assembly. The swift reversal of the decree, however, prevented any significant violence, leaving the nation grappling with the aftermath and the profound political implications of this unprecedented event. The resignation of Han Dong-hoon underscores the deep crisis that engulfs South Korean politics, the future of which remains uncertain and heavily reliant on the constitutional court’s forthcoming decision.

South Korea ruling party leader steps down after backing impeachment of President Yoon

Announcement by Han Dong-hoon comes as constitutional court prepares to review parliament’s vote to impeach Yoon Suk Yeol